Analog Illusions

Chapter 8: Birth of the pixel

Dear friends,

This is a good one… In today’s chapter of User Zero I get to tell you why pinball was illegal until the 70s and the story behind the rise of the very first video games. Fun stuff.

Speaking of analog illusions (but through a completely different lens), I have been creating holograms that have been infesting Mountain Dew cans, Wendy’s cups, and my refrigerator inside Coke bottles. If that is your kind of weird, you should follow me on Instagram. More next week. Stay creative.

Your friend,

Ade

“Humanity is acquiring all the right technology for all the wrong reasons.” —Buckminster Fuller

Aliens surveying a post-apocalyptic Earth will easily deduce the purpose of the hammers they find, but their superior intellect may never get past the lock screen of the iPhones littered among the smoldering wasteland.

The smart phone in your pocket has become one of, if not the main input for human brains. There has never been a machine as intimately connected to our bodies. Despite its millions of tiny lights, each capable of displaying millions of colors that change by the millisecond, smart phones still struggle to match reality. So far. The realistic graphics, the buttery-smooth animations, the illusion that your fingers are actually pushing and pulling the objects on your screen — the gap between analog and digital gets smaller with every software update.

And yet there is still something dazzling about well-made analog machines. Take pinball. Remember how it felt to drop a quarter into a slot, to hear it clank against the switches that brought the machine to life? You would pull the spring back and let go. The ball exploded up the slide and flipped around the board. The lights, the sounds, the vibrations, all the rich details are perfectly designed to titillate the senses. As the ball fell towards the abyss, the tension and anticipation was palpable. You would slap the button to engage the flipper at the critical instant and the ball ricocheted back to the top of the board and the adventure repeated. Twenty-five cents is a steal when you consider the dopamine hit that pinball delivers. It should be illegal. And in fact it was illegal for most of the 20th century.

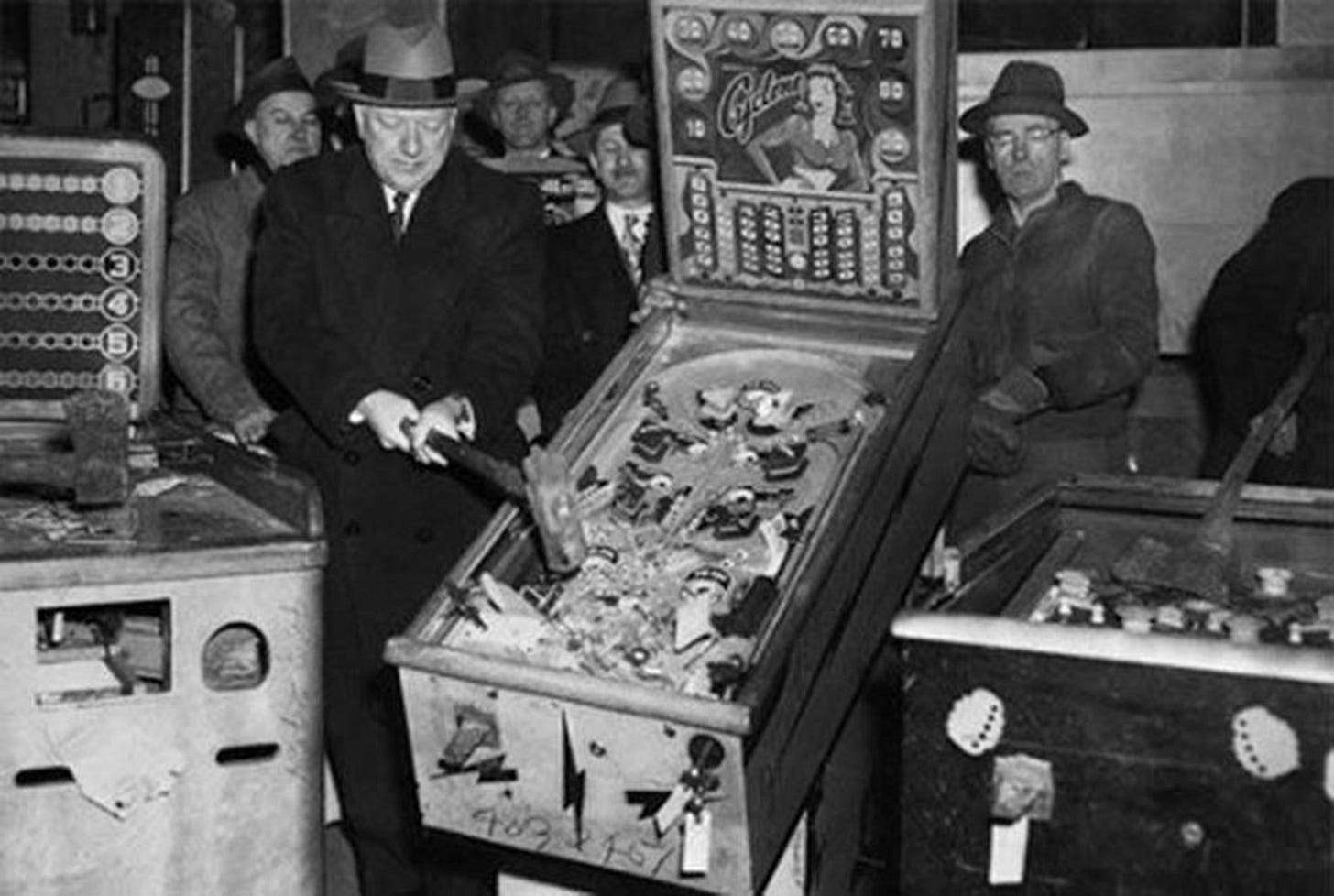

In 1942, the mayor of New York City confiscated 2,000 illegal pinball machines. The addicting machines were smashed with sledgehammers, stripped of all usable metal, and their remains were dumped in the Hudson River. In those days, pinball machines were gambling devices. You put a nickel in the slot and if you were lucky, the ball randomly rolled into a winning slot and you would hit a jackpot. Sometimes you won, usually you lost, just like a slot machine. That gamble was what caused the moral outrage.

In 1947, a modification to the user interface was introduced that transformed pinball from a game of chance to one of skill. Humpty Dumpty was the first pinball game with flippers. The lines between skill and chance were blurred. It would take another 25 years before the ban on pinball machines would be lifted in New York City, Chicago, Los Angeles, and cities across America.

In 1972, about the same time that pinball was regaining legal status, an unlikely competitor appeared next to pinball machines in a bar in Sunnyvale, California. Behind a tall cabinet, a small black and white television presented a thick dotted line. Insert a quarter and a tiny square jumped from the line, shooting toward the edge of the window. A slab of light collided with the pixel, bouncing the metaphorical tennis ball back across the void. This was the first blockbuster video game, Pong.

If you had been in that tavern you probably would have written off Pong as a novelty act. Sure, it was fun, but compared to the extravaganza happening inside a pinball machine, Pong was just a crude brick of light. Even those who sensed the coming tide shift to digital wouldn’t have been able to predict the marvel of your smartphone.

Pong’s success was due in no small part to the simplicity of the metaphor. The small square was a ball. The rectangle on the edge was your racquet. You turn a knob to move your rectangle up or down, attempting to prevent the ball from getting past you. The user interface mapped cleanly to mental models.

One might assume that the simplicity of Pong was based entirely on the limitations of the primitive computers and screens of the time. The constraints are an important part of the story, but they don’t explain the success of Pong. To understand Pong’s meteoric rise, we must contrast Pong with its predecessor, another digital video game called Computer Space. While Pong remains a household name half a century after it was invented, Computer Space is unknown to all but the historians of video games. Why was Pong so successful while Computer Space failed?

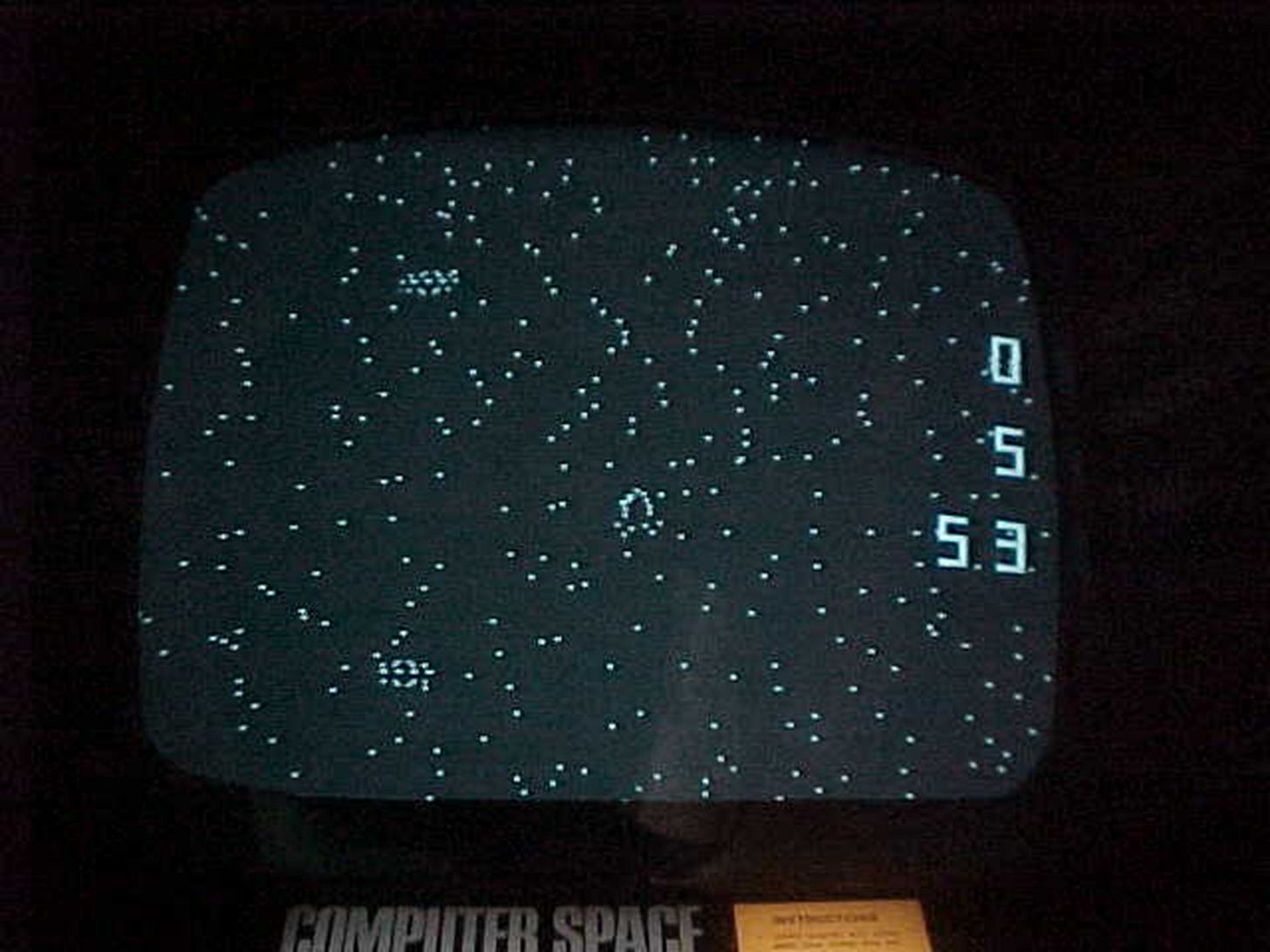

Compared to Pong’s minimalist game play, Computer Space was light years ahead. Where Pong’s controls consisted of one rotating knob per player, Computer Space had four buttons. Button one fired a missile. Button two controlled your thrust. Buttons three and Four rotated your ship right or left.

The graphics of Computer Space were also more advanced. Where Pong’s graphics were made entirely of squares, Computer Space had a star field containing your space ship and two alien enemies adorned with rotating lights.

In terms of audio, Pong only made three sounds, tink, dink, and bonk. Computer Space on the other hand blasted clicks and beeps constantly in different combinations to simulate, as best it could, war sounds from outer space.

As our study of user interfaces continues, an important lesson is that simplicity usually wins. And not just simplicity, but simplicity that maps easily to mental models. A limited number of pixels was a constraint that forced video game makers to reduce complex ideas to simple shapes. In order for this abstraction to work, games needed to build links between the chunky pixels and people’s mental maps. The concept of tennis was an easily grasped metaphor. It naturally mapped to an already understood concept, a bouncing ball. You don’t need to be a science fiction fan, or a rocket scientist for Pong to make sense. Then, with an understanding of the game in mind, the simplicity of the controls of the game come into play. Compared to Computer Space’s complex matrix of buttons, the affordance of Pong’s controller, an intuitive rotating knob, was simple to learn.

Computer Space lost to Pong despite being first to market. If you happen to be in the software business, you have probably heard of minimum viable products (MVP), an approach to software design that encourages creators to ship their work at the instant that it delivers value to the end user. Was Pong a minimum viable product? It might be tempting to think so, but history tells a different story.

Magnavox created the first commercial home video game console called the Odyssey. It shipped in August 1972, essentially the same time that the first Pong machine’s cabinet was getting pumped full of quarters in that bar in California. The Odyssey came with a game called Table Tennis.

Magnavox's game had no sound. It couldn’t keep score. Where Pong’s ball was precise, Table Tennis was looser and the ball could be warped with the joystick after it was struck making for a less realistic effect. Pong’s ball bounced off the top and bottom of the screen, while Table Tennis let the ball go out of bounds. These details may seem trivial, but they aren’t. They are the difference between a game that draws eager crowds at a bar and a game that gathers dust in your attic. You can feel these differences. Table Tennis, the MVP version of Pong, was crushed in the court of public opinion.

The superior experience of Pong wasn’t enough to protect it from lawsuits, however. Magnavox filed a patent infringement suit against Atari and several other companies who had built Pong knockoffs. Pong settled the claim and legally sub-licensed the intellectual property from Magnavox. While the Odyssey’s home console would struggle to remain relevant it would go on to win $100 million by suing the hordes of Pong copycats that emerged in the wake of Pong’s success.

We still remember Pong, while the Odyssey is forgotten. In hindsight the fat pixels inspire nostalgia and it can be easy to overlook how revolutionary the early video games were. Our digital acumen has become so advanced that we take for granted how complex today’s computers are.

The mind’s ability to map simple shapes to complex ideas is the foundation that modern technology is built on. That fat white square became a tennis ball in our mind. The windows that open and close on the computer screen build on our understanding of windows of our house. We use metaphors of files, folders, and trash cans because these affordances provide real-world metaphors that our brains can latch on to.

When an illusion is perfect, we are completely fooled. We bounce back and forth between digital and analog realities like a tennis ball in Pong. The food we eat is real. Ping. The better-than-reality photo of your dinner that you post on Instagram is fake. Pong. But the dopamine you feel when someone likes that photo is as real as the stimulation your tastebuds felt as you ate it. Ping. You know that the image you curate on Facebook isn’t real. Pong. But the comments on your timeline sting just as hard as a slap across the face. Ping.

The next evolution of digital technology will push beyond pixels on a screen and into the depths of our minds. Call it virtual reality, augmented reality, artificial intelligence, or whatever buzzword is in style, but reality itself is changing. Our capacity to be fooled by this illusion, our vulnerability to invisibility blindness is the subject of the next chapter.