Deadly UI

Chapter 11: The evolution of a killing machine

Dear Friends,

Yesterday my friend was telling me about his car troubles. It wasn’t a mechanical issue, it had to do with his key fob. He described a YouTube video that explained an odd set of rituals he would have to perform in order to manually “reboot” his car.

If you’re like me, this story makes your blood boil. How did we arrive at this place where our possessions render us helpless every time tech fails? This week’s User Zero chapter tries to answer that question. Strap in and let me tell you the story of concept horse carriages, tragic car design fails, tractor hacking, and the best and worst of Volkswagen. I hope you enjoy it. Stay creative.

Your friend,

Ade

“All the research and development of all the products and services that are going to affect all of our forward days, are now being conducted in the realm of the electromagnetic spectrum reality, not directly apprehendable by any of the human senses.” —Buckminster Fuller

In science fiction you can teleport out of danger, but on Earth when an unmanned crossover rolls in your direction you need to get out of the way. That is how Anton Yelchin died, crushed against the gate in his driveway. You may remember Anton from the 2009 Star Trek reboot where he played Chekov. While the tragedy made headlines around the world, the design flaw that lead to his death mostly avoided scrutiny.

Take a look at the following maps showing variations of the most common user interfaces in the world. Do you recognize them? Even if you figured out that these diagrams represent automobile shifter positions, I am willing to bet that it wasn’t an instant association.

Now look again at the diagrams and try to match the actions of each white dot with their corresponding letters. This exercise is challenging because your mind has to stumble through every vehicle you have ever driven, remembering exceptions and variations to the patterns. You may find yourself thinking things like, “Well, my dad’s truck had reverse in the upper right, but my sister’s car had it in the lower right. Which kind is this?”

If you’ve never learned to drive a manual transmission, your mental models are even more abstract. An automatic vehicle eliminates your need to understand how different gears affect your control of the vehicle. The ideas in your mind are mapped to different concepts than the words that correspond to the letters on the shifter. When we learned to drive we remapped the manufacturer’s abbreviations to how we actually perceive movement. Our mental maps look like this:

P = Park = Stop

R = Reverse = Backwards

N = Neutral = Roll

D = Drive = Go

L = Low = Slow

S = Sport = Fast

You are so good at this shortcut that you never think about it. And while the cognitive load may be minimal, it adds up. Car interfaces are some of the most widely used systems in the world. Billions of us use it every day without giving it much scrutiny.

Anton Yelchin died because of an “innovation” in shifter design. He was the victim of deadly user interface design. Anton believed his Jeep was in “P = Stop” mode and got out of his vehicle. He didn’t realize the Jeep was actually in “N = Roll” mode. Tragedy followed.

Anton’s confusion sprung from a new shifter design called a monostable shifter. The position of the monostable shifter is stationary. To know what gear your car is in you must reference a digital screen for confirmation. The muscle memory that older shifters take advantage of was stripped from the system. This may seem trivial, but this extra check is the difference between life and death.

The death of a celebrity is highly visible, outrageous, the kind of thing that focuses our attention on the danger of driving. This is important, but we should look at the negative space. We are safer today partly because of dramatic changes to the car (airbags, anti-lock brakes, etc.), but much of the safety is a result of the car remaining unchanged. The invisible part of the story is every driver who is alive today because of the standardization of automobile controls.

Sit in any vehicle and you can pretty much make it go. It isn’t perfect, but within minutes your body adjusts to the variation in gas pedal pressure, the feel of the breaks, and the adjusted position of the controls. Muscle memory is why standardization has been able to save billions of lives. We count tombstones, but the body count of living drivers is invisible. The invisibility of standardization leads to reckless abandonment of manual controls in favor of new patterns.

When a modern car company replaces several physical controls with multi-purpose touchscreens it feels like they are simplifying the design when in fact they are introducing new complexity. Tesla vehicles, for example, have eliminated many physical controls because the touchscreen can manage so many tasks from a single screen. The design appears as modern as a smartphone, but we fail to realize how critical tactile feedback is to safely controlling dangerous machines. Our sensory systems can extend deep into the tools we use. Touchscreens sever that bond.

The redeeming characteristic of the traditional gear shifter systems is that they are combined with strong tactile feedback. When you get in your car, muscle memory takes over. Your hand instinctively knows where the controls will be. You pull the lever with exactly the right amount of pressure and you feel the moment that the knob clicks into the right spot. You don’t have to look down to make sure the “D” is highlighted. Your mind doesn’t have to reference your mental map or do the “D=Drive=Go” translation.

The monostable shifter replaced physical feedback with a “simpler” design and the result was confusion. It has been implicated in 117 crashes and as many as 41 injuries. After Yelchin’s high profile tragedy all 811,586 vehicles containing the monostable shifter design have been recalled. Recalled vehicles will still have the monostable shifter, but a software update will prevent the vehicles from rolling when the vehicle is in gear and the driver’s door is open. This may prevent some runaway vehicles but it does nothing to address the design flaws that made the shifter confusing in the first place.

The monostable shifter is a single design flaw in an incredibly complex system. More than a million people die each year in car accidents. Another 50 million are injured. Despite this staggering carnage and the public demand for improvement, the solution is unclear. Is it better to cling to the standards of the past or abandon the familiar in search of new, better designs? This is the unavoidable tension between tradition and innovation. The safety provided by standardized car design is undeniable. Equally undeniable are the safety improvements from new technology that has abandoned the designs of the past.

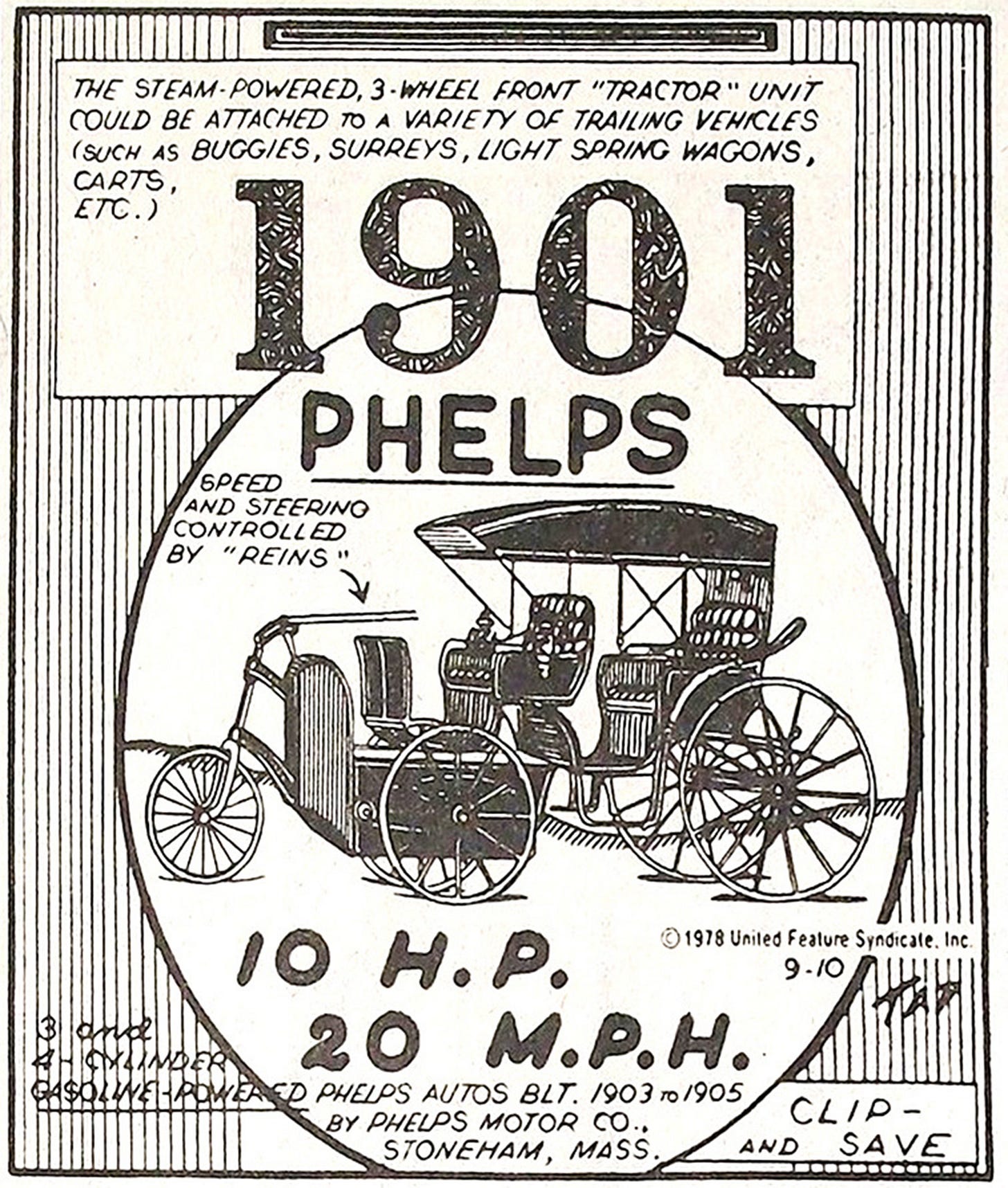

In 1900 the user interface of automobiles was far from standardized. If you were an inventor in the pre-car era, how would you go about appealing to doubting consumers? You might appeal to his sense of the familiar. Instead of automobile you might use words like horseless carriage so that the disruptive technology felt like a simple extension of existing transportation.

You might go as far as to incorporate the user interface of the horse into the design of your car. That was the approach attempted by L.J. Phelps. Rather than intimidate buyers with a complex set of unintuitive controls, the Phelps car was controlled by reins.

Advertisements proclaimed, “If you can control this horse, you can drive the Phelps car.” As ridiculous as this sounds, there is logic behind this approach. It is not unlike the first metaphors on computer screens that mimicked a desktop, folders, files, and a trash can. These familiar concepts helped people understand an abstract machine. We take our steering wheels for granted, forgetting that they were once novel user interfaces. To calm cautious drivers, the Phelps car avoided the foot pedals and steering wheel in favor of controls people were already comfortable with.

When you are used to driving a horse-drawn carriage, stomping on a brake pedal is less natural than pulling on the reins. When turning your horse drawn carriage is mentally mapped to the action of pulling the reins right or left, the act of turning a wheel requires burning new neural pathways. It’s not hard, but the new mental model is not without resistance. Similarly, as we debate a future of self-driving vehicles, we feel discomfort with the idea of releasing the wheel. If the future of cars is self-driving, perhaps future generations will struggle to understand the appeal of our primitive steering wheels.

Riding a horse wasn’t particularly safe, so perhaps it shouldn’t surprise us that safety wasn’t necessarily a selling point of the first cars. It takes public outrage to bring about safety improvements. Today it takes the death of a movie star to cause outrage, but as cars began crowding the streets it was the death of children that made headlines. By the 1920s, 60 percent of automobile fatalities nationwide were kids under age nine. Paved roads with painted lines, stop signs, brake lights, speed limits – all the safety mechanisms baked into our modern road systems, weren’t designed in parallel with the car, they adapted separately, fueled by the painful stories like those of parents whose babies were mowed down in front of their homes. As we approach a future of self-driving cars we should remember that technology tends to drive blindly into the future, it often takes tragedy to open our eyes.

From the beginning, dominance in the car industry has typically been less about safety than reliability. Whoever can build the car that can last the longest with the least amount of maintenance interference tends to be the top seller. The Phelps car also leveraged fears that machines break down, claiming that their vehicle was “as reliable as a good horse, but cheaper to maintain.” It may seem odd to think of horses as low-maintenance, but when horses were the dominant mode of transportation, taking care of horses was a part of daily life. Yes, it was a hassle, but it was a known hassle. Fixing a machine required knowledge that the average horse owner didn’t possess.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that the best-selling vehicle of all time prioritized reliability over safety. When your 1970 Volkswagen Beetle breaks down, any mechanic worth his wrench should be able to get your love bug back on the road. There was a time when the guts of a car were accessible. The straightforward design of the Beetle kept it in production with little change right up until 2003 as hybrid vehicles were gaining traction. Its record run of 21 million cars produced with only light modifications over 50+ years will never be broken.

The Beetle was mechanical, every part could be disassembled and put back together. Automobiles have evolved from mechanical machines to digital computers. Sure, Beetles weren’t self-driving (excluding Herbie) but you could pull them apart and see what made them tick. Car maintenance has been reduced to knowing that a red icon on the dashboard means you need to take it to an expert who understands the mysteries of the machine. Your car’s engine is opaque, a system so complex that few of us can diagnose, let alone repair it without training. As technology advances under the hood, each component becomes more opaque until even the specialists don’t fully understand them. A mechanic doesn’t need to fully understand a complex component, he simply needs to swap out the part that the computer tells him is malfunctioning.

Following this evolution, mechanics have transitioned from generalists who could fix anything to specialists who get uncomfortable working on anything other than their chosen brand. Even the best of these mechanics won’t touch the code behind the curtain of your car’s computer.

Today the average new car has ten million lines of code. Not only is it impossible to reverse engineer the code of our cars, even attempting such an activity has become illegal. The code in your car is locked down and protected by digital encryption. Breaking the encryption requires breaking the law.

The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (1986) made it a crime to violate a company’s terms of service. Attempts to “look under the hood” of computerized products is illegal. To alter the code will immediately void your warranty but it also risks retribution by car companies if they decide to enforce their copyright. You probably won’t go to jail, more likely the object you are fiddling with will become a brick once the self-aware software detects that it is being fiddled with. Currently the only people willingly to accept this risk are performance obsessed tinkerers who fearlessly modify the code of their cars. Soon even these tinkerers may become extinct.

Cars aren’t the only machines that have been swallowed by software. The internet of things is bestowing formerly benign objects with computerized components. We invite products into our homes that contain cameras, microphones, sensors, and an internet connection that allows them to phone home and transfer whatever data the mother ship requests.

As technology becomes more and more opaque, the likelihood that devices will manipulate us has never been greater. Even the watchdogs are being fooled as software gets better at avoiding detection. Volkswagen evaded emissions violations for years by equipping their vehicles with software that could recognize when they were being tested for emissions and adjust their engines on-the-fly to switch into a more efficient mode. Cheating is inevitable, and everywhere that software can be used to game a system it will. If it isn’t happening already, fraudulent functionality is only a software update away. Out of the box, a device may be neutral, but code changes can happen silently in the background, altering the product for uses you don’t authorize.

Take your printer as an example. The money you believed you were saving at checkout is quickly drained when it comes time to refill the ink. Your attempts to find cheaper ink are thwarted because the self-aware printer is programmed to prevent you from using “unapproved” ink.

This extends beyond consumer products. The price of a John Deere tractor can exceed $800,000 but owning that vehicle doesn’t come with the right to repair it yourself. Just like your printer, the software within the tractor knows if replacement parts have been authorized.

If a John Deere machine breaks down mid-harvest, a farmer’s only option is to contact the nearest dealership. While this appears to be a greedy money grab, the situation is more complicated.

Modern tractors are marvels of technology. They are capable of placing seeds inches apart while traveling at ten miles per hour. They can retrace their tracks perfectly in future visits to the field, applying varying rates of fertilizer depending on the needs of different areas of the field. At harvest, each plant contributes its bounty, completing the growth cycle. The yield is measured, analyzed, and cross-referenced with every pass the tractor made across the field. Did I mention that they are essentially self-driving?

Building a machine this complex requires innovation at the factory. The assembly line of Henry Ford has evolved. If you tour a John Deere factory you will see raw steel entering on one side and complete tractors coming out the other. Within this system, the accuracy and tolerances of the machines are as close to perfection as humans may ever achieve. The tools that built the tractor are computerized and record data for every action. When a tractor leaves the factory, the torque of each bolt is known. They know the person who turned the wrench and at what instant the bolt was added.

While we can relate to the frustration of a farmer whose attempts to repair his own tractor are blocked, we need to realize that our machines are evolving beyond anything that we could ever hope to understand.

This is our reality. We only understand our tools at an abstract surface level. We recognize symbols and memorize button sequences. Our role is simply to watch for check engine lights. When our regularly scheduled broadcast is interrupted because a movie star is killed by his car, we become enraged. We demand safety. Hopefully there are still people around who understand our systems well enough to repair the damage. That knowledge seems to be slipping away.

There comes a point where technology ceases to augment human weakness and instead replaces our cognitive strength with something weaker. One generation grows up comfortable under the hood of cars where any part can be swapped out and maintained. The next generation might be able to pop the hood, but can’t tell the carburetor from the fuel pump. And the generation after that? Driverless cars will allow us to forget how to use a steering wheel. Mechanical competence has been replaced by blind reliance on things we can’t understand.

Do we call these technological advances evolution, or is it something else? Survival of the fittest conjures an image of a strong alpha that withstands the pressures better than weaker counterparts. In reality evolution is just math, a stupid calculation that depends on raw numbers. Given a large enough population, the stupidity of a culture can be nearly limitless and survival is practically guaranteed. Personally, this give me little solace.

Modern car designs feel like human triumph but the danger hides in the negative space. To praise the pioneers that invented the automobile is blindness. We idolize Henry Ford, forgetting the children wrapped around axles, the mangled men in the streets, the carnage blessed by machine-obsessed consumers.

We can criticize our primitive ancestors, claim moral superiority, but if we think we won’t make the same mistakes again then we have learned nothing from evolution. Evolution depends on blindness. It requires fools to fall face first into folly, oblivious to the gears that will crush them out of existence, only to be replaced by new actors in the sequel.

The path to progress marches straight through incompetence. The person walking the street with their eyes glued to their phone is begging natural selection to make a calculation. Do people who text and drive deserve to be in the gene pool? And do the rest of us have the will to systematize our tools to protect ourselves from these fools? The gaps in the negative space of our minds leave us vulnerable to predators. We are prey for conmen who can see a sucker from a mile away.