Deep Fake

Chapter 16: Five surprising tricks for coconut removal

Dear friend,

First, a plug for my YouTube channel. If you haven’t heard about my ongoing video series involving cassette tape experiments, now you know. It’s called “Ade’s Tape Breaks” and I’ve got a dozen videos so far involving lofi, analog audio experiments with magnetic tape. It has been really fun and I invite you to check it out and tell me what you think.

This week I am sharing with you the chapter in User Zero about deep fakes. High points include Dave Chapelle’s bad memory, the truth about lemmings, DIY monkey traps, the documentary Disney doesn’t want you to see, and the tragic story of an unlikely movie star. And I don’t mention AI even once. Thanks for reading. Stay creative.

Your friend,

Ade

“Nature is trying very hard to make us succeed, but nature does not depend on us. We are not the only experiment.” —Buckminster Fuller

On April 17, 2018, President Barack Obama delivered a chilling warning describing a dangerous new technology. He singled out software so advanced that it could generate realistic video showing people doing and saying anything that the creators wanted. Obama said,

“We’re entering an era in which our enemies can make it look like anyone is saying anything at any point in time... This is a dangerous time. Moving forward, we need to be more vigilant with what we trust from the internet.”

If you have seen the video, you already know the punchline. The video itself is proof of the dangerous technology. The footage is a fake Obama being voiced by comedian, Jordan Peele. The illusion is so convincing that had it not been for the absurd language and the mid-video split screen showing Peele, the president’s fake address might have gone undetected.

It was inevitable that we would reach a point in time when video could be altered as easily as still photos. Deceptive editing has been employed for decades, the difference now is that video can be delivered without cuts while the speaker never breaks eye contact as you are deceived. As we ascend out of the uncanny valley, fake Obama’s words ring true. We do need to be more vigilant about trusting our eyes.

Back when I photoshopped RVs into picturesque landscapes, I rarely questioned the morality of these illusions, even in the most deceptive situations. One summer I flew to Las Vegas to photograph an expensive dune buggy driving up the ramp of a toy hauler. When the car’s giant rear tires made it half way up the ramp, the metal began to bend under the weight of the vehicle. Aside from the damage to our product, I wasn’t worried. I photographed the scene and promised the concerned crew that I would fix the bent ramp in Photoshop.

With one fraud under my belt, I proceeded to complete my second assignment. I left the dealership and headed north in search of sand dunes that I could Photoshop into the background of the toy hauler brochure. The temperatures were well above 100 degrees when I pulled off the road and headed towards a sand dune in the distance. Several miles into nowhere my car got stuck in the sand. My phone was inconveniently dead and if I hadn’t been able to dig my car out, someone might have found my dried carcass stuck to the leather seat of a rental car, dead in a cocoon of technology that couldn’t save me.

Why is it that a foolish man with a $5,000 camera and reality-altering Photoshop skills can die of thirst in Las Vegas while tribes of primitive people at the equator can survive for centuries? How do you find water in the desert? The user interface of Earth is opaque until you learn the secret survival skills. People can survive in the desert, if they know the user interface.

To find water in Africa, a hunter places melon seeds in a hole just large enough for a monkey’s arm. When the curious monkey reaches into the hole and grabs the seeds, its fist is too large to pull out of the hole. Trapped, the monkey doesn’t realize it could simply free itself by letting go of the food. The hunter places a rope around the monkey and gives it a treat, chunks of salt which the monkey eats like candy. The salt in turn dries the monkey’s mouth and the desperate animal leads the hunter to the secret watering hole.

How would you go about testing the accuracy of this water-finding advice? Is this folklore or an actual strategy that could save your life? If I told you the story was filmed in a documentary would it lend credibility to the tale?

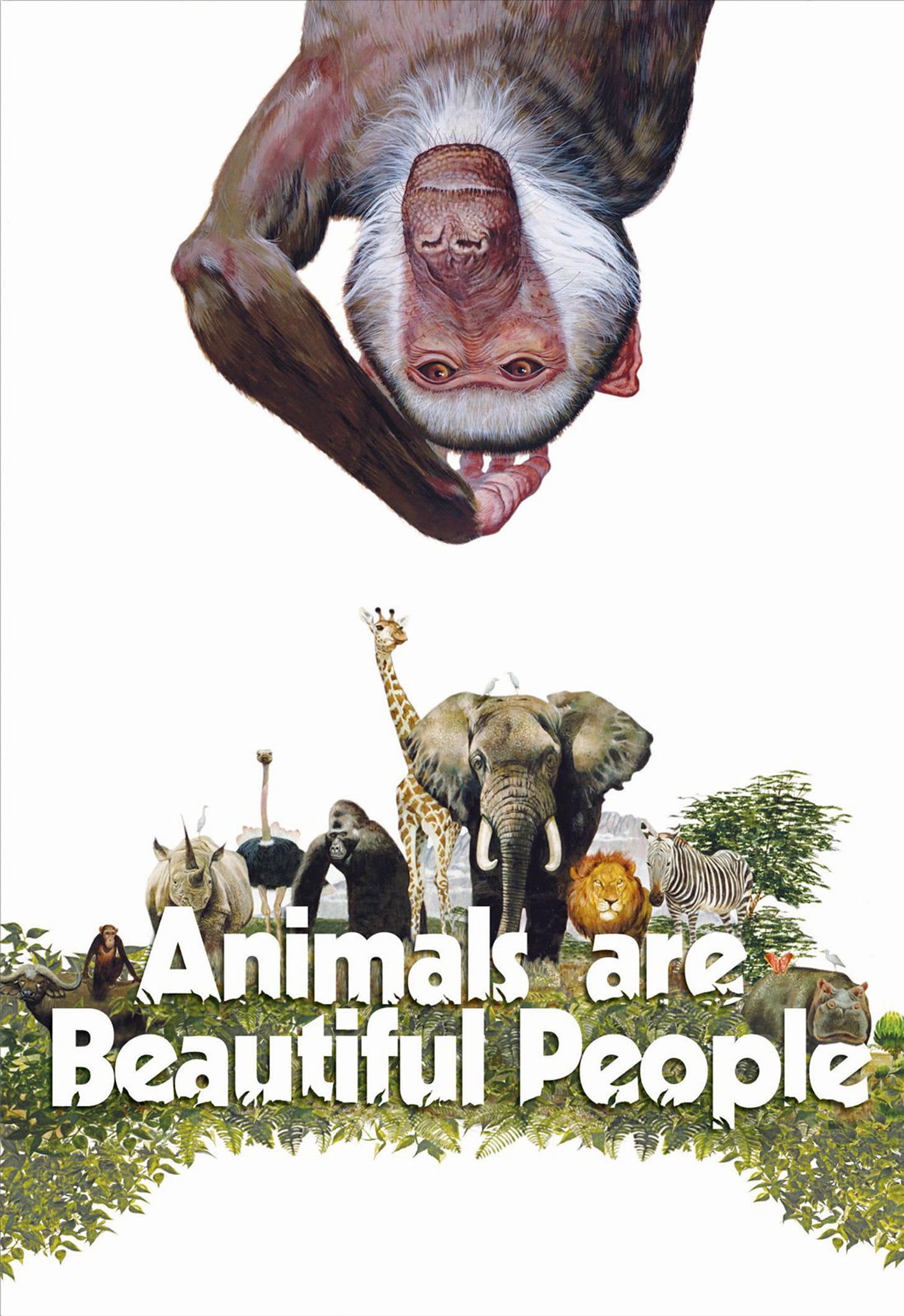

Comedian Dave Chapelle told a version of the monkey salt trap story during an interview on CBS This Morning. Chappelle used the analogy to explain why he walked away from millions of dollars when he left his hit show. He said, “I felt like the baboon, but I was smart enough to let go of the salt.” He described having heard the story from a nature show.

The nature show Chapelle references was most likely Animals are Beautiful People, a 1974 film by South African director Jamie Uys which contains the baboon story. Jamie Uys is not a naturalist, he is a story teller and entertainer. Animals are Beautiful People juxtaposes humorous video of African animals with serious sounding descriptions from a voice with a British accent. While the monkey trap may have had roots in folklore, the video was completely fabricated. We are familiar with the mockumentary genre today, but in 1974 comedy films disguised as a documentaries were just catching on.

We welcome deception from mockumentaries, but we expect more from real documentaries. And yet even the best-intentioned nature documentaries employ extremely deceptive tricks of editing to create the illusion of nature. The majority of sound in nature films is artificially added in post production. In some cases the script is written first, then footage is found that supports the narrative.

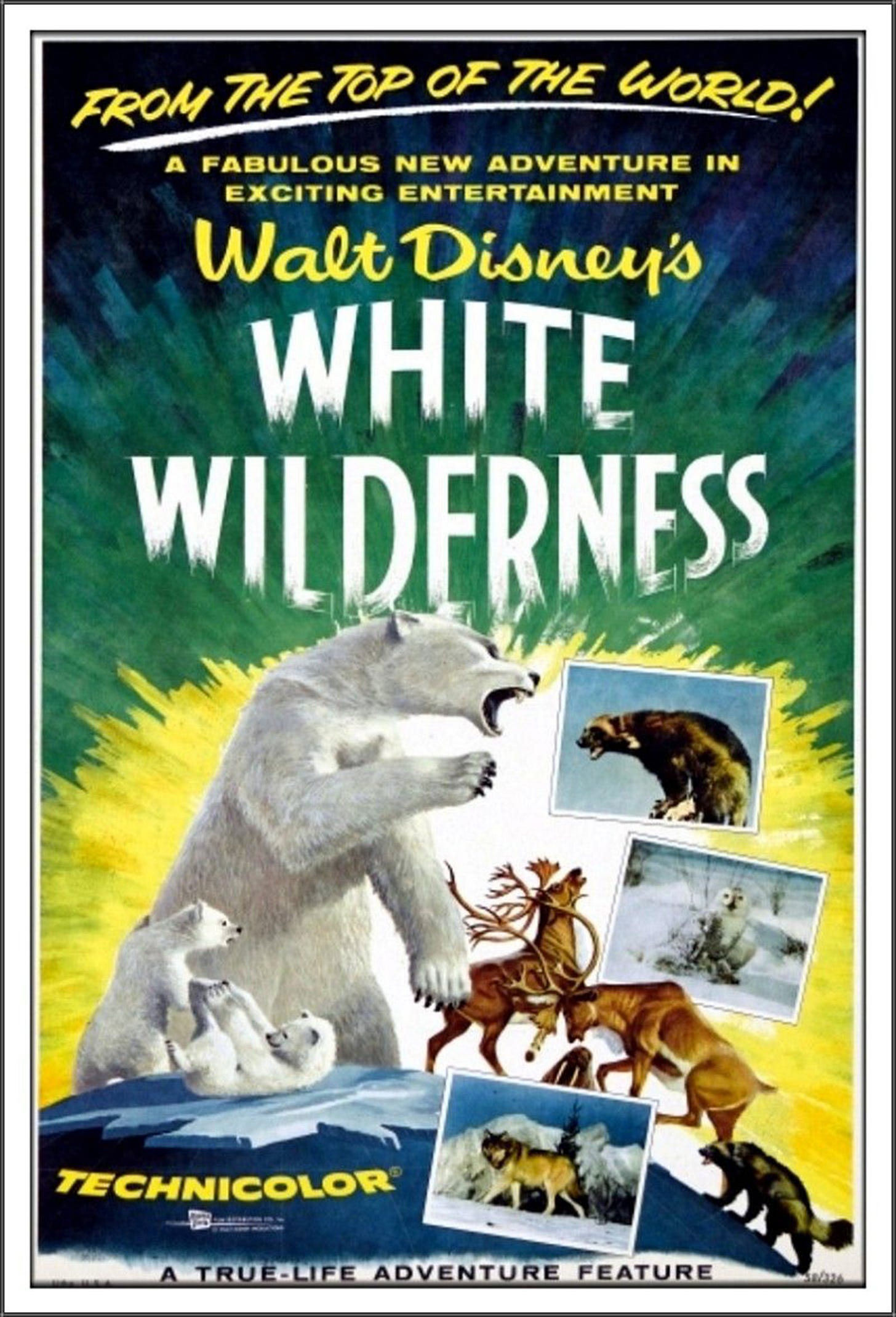

The 1958 Disney film White Wilderness won an Academy Award for best documentary feature despite its reliance on fabricated storylines. Most notable among the faked footage is a story about lemmings. Today, we use the word lemming to describe a person who unthinkingly joins a mass movement, especially a headlong rush to destruction. In nature there is little evidence that actual lemmings are suicidal. The stereotype seems to have arisen not out of scientific observation of lemmings, but because of the popularity of White Wilderness and the faked footage of lemmings jumping to their deaths.

To create the lemming suicide scene, the film crew of White Wilderness backed a truck loaded with lemmings up to a cliff and dumped them over the edge. The director carefully hid the truck off-camera and allowed the narrator to describe how the animals were, “casting themselves bodily out into space.” The mass-suicide myth is explained as an attempt by the animals to reach the distant shore of a more hospitable land where their species can thrive. The number of lemmings swimming for their lives decreases as the weak swimmers drown. Finally, the few remaining lemmings step onto the shore, brave heroes in a manufactured fiction.

We accept video as truth, but even in the most trustworthy of sources, there will always be truth hidden off camera. Video footage is opaque. Regardless of where you enter this story, it is impossible to get the full picture. As stories get retold, a certain amount of data is lost. Each remix alters the story, in some ways enhancing it, in other ways diluting it. It is hard to judge the effects of this fidelity loss.

Whether it is a presidential address, documentary footage, or a news clip, we should be skeptical. As the sources of video are increasingly obscured, the quality of video is increasing. We are on the verge of a new evolution as special effects are indecipherable from real video and the cost of production continues to plummet. The result is a video landscape that is opaque, where the average person has lost the ability to tell what is real from what is manufactured and we have no idea a deception has even occurred.

The news isn’t all bad, in fact the unmasking of fake video may actually work to our benefit. Video has never been reality. That was an illusion. There has always been deception hiding just off camera. The motives were unknown and invisible. Soon we will be fooled by video so regularly that we will cease to consider it as truth. We will recognize it for what it has always been, a medium of deception.

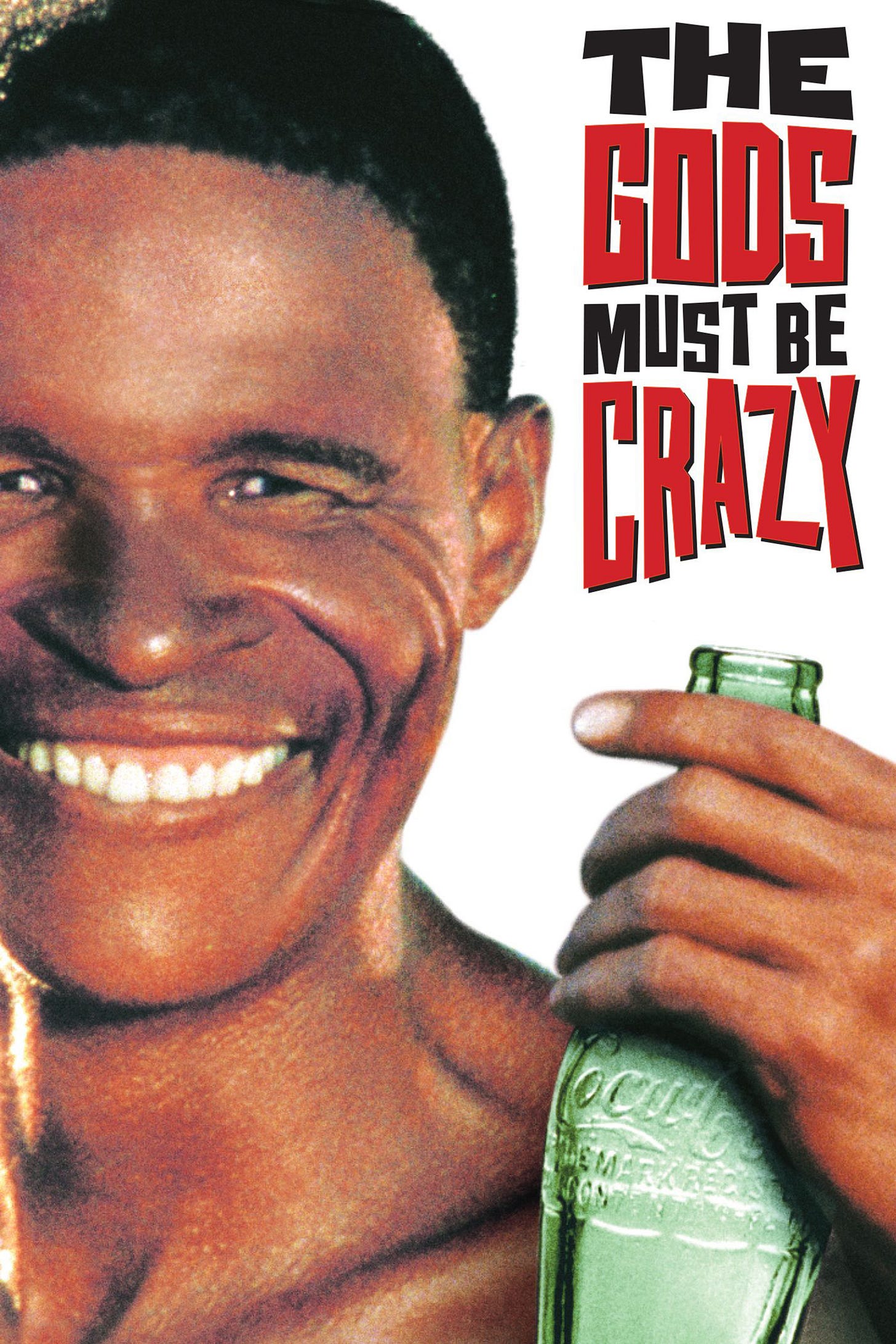

The two minute clip containing the baboon scene from Animals are Beautiful People has been posted many times on YouTube, usually without attribution or description. Presumably the source is intentionally left off to avoid detection from YouTube’s censors who prohibit posting of copyrighted materials. These clips are often accompanied by advertisements. Even a mildly popular YouTube video with ads can earn more money than the star of another film by Jamie Uys, The Gods Must Be Crazy, made in 1980. The film is a comedy whose plot centers around a Coca-Cola bottle that falls from a plane and lands in an African desert where it disrupts the culture of a primitive tribal community.

The true story behind The Gods Must Be Crazy could pass for a sketch on Dave Chapelle’s show. The actor in The Gods Must Be Crazy is N!Xau (pronounced En (click) ow), an actual bushman from Botswana. N!Xau was paid $300 in cash for his first ten days as a movie star. Unfortunately, the money was useless in N!Xau’s village and the money blew away. Future payments were made in cattle but the majority of these cows were eaten by lions. While filming, N!Xau developed a smoking habit and an affection for Japanese sake.

Without the cultural literacy to see the trap, N!Xau’s hand clutched onto the prize of fame. He ate the treats provided by the film’s creators who put him on a leash. He lead them to water, as The Gods Must Be Crazy became the most commercially successful movie in South Africa's history based on the performance of a man who reportedly couldn’t count past twenty.

We believe we are more advanced than bushmen, and yet it is easy to see ourselves in N!Xau’s situation as well as the monkey trap parable. We only see the trap after it is too late. What mechanisms can we use to avoid this fate?

Once again I will reference Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, where Robert Persig describes a similar monkey trap. In Persig's version, the animal’s fist is stuck in a coconut clinging to rice. Persig’s question is “What general advice could you give the monkey that would help him understand his situation?” Our instinct is to scream at the monkey, “Just let go of the rice,” but that is to solve the problem for the monkey. How do you equip the monkey with a mental system that allows him to solve the problem by itself? Persig’s solution is to develop a value system that allows you to weigh the invisible benefits of freedom against the tangible rewards of the rice you hold in your hand. In other words, we need to learn how to evaluate the problem as user zero.

Our education is built around the memorization of answers. The reason you are stuck isn’t because you slept through the “how to escape coconut traps” lecture. No, our education failed to equip us with mental systems that can overcome unknowable dangers. Oblivious, we accept our fate, walking around with coconuts permanently attached to our arms, waiting for someone to tell us the secret “let go of the rice” technique. Maybe we will stumble across a blog post explaining “Five surprising tricks for coconut removal.”

To frame this in terms of affordances and opacity, we are trapped by affordances that promise rewards not realizing they will refuse to release us from their grasp. The traps are invisible and the escape mechanisms are opaque. The gifts of technology fall from the sky like Coke bottles. We thank the gods for their inventions but lack the ability to reverse engineer their intentions.

Once you realize the negligence of our educators to properly prepare us for problem solving, another metaphor becomes dangerously relevant. We are lemmings. No, we aren’t blindly following our peers off a cliff, we have been loaded into a truck, White Wilderness style, and dumped into the void. All the while the cameras are rolling and nobody can figure out if this is a comedy or a documentary. If only our brains could detect the fakery, if only our mental hardware came with a check engine light to alert us to mental malfunction.

Next week: Chapter 17 - Check Engine Lights… Stepping into the opaque