Dear friends,

If last week’s chapter ruined bicycles for you, today I get to rewire your brain about playgrounds. Will you allow me to spin your mental merry-go-round beyond the comfort zone? Hold on tight. Stay creative.

Your friend,

– Ade

“If you want to do something nice for a child, give them an environment where they can touch things as much as they want.” — Buckminster Fuller

German bombers opened their bellies above London, dropping terror designed by Hitler to break the British will. Failing that primary objective, The Blitz succeeded in decimating the cities of the United Kingdom, leaving wreckage that would take decades to rebuild. Evacuations forced four million people out of their homes and when the families returned, they were confronted by rubble – piles of bricks and ashes, twisted steal, splintered wood beams, carcasses of cars, and trains whose twisted spines no longer clung to the tracks.

This is an odd landscape to find inspiration. And yet here, in the most unlikely of places you would find children playing. As the city was rebuilt, the bomb sites became junkyards filled with raw materials that the children transformed into playgrounds. Makeshift forts, teetering towers, tunnel systems – structures whose only limits were the children’s imagination – sprung up from the wasteland.

The improvisational spirit of children to play with whatever material they have on hand seems to be a fundamental part of mental development. Carl Theodor Sørensen, a Danish landscape architect, abandoned his traditional approach to playground design after he was forced to admit that children preferred to play everywhere but in the playgrounds that he designed. During Denmark’s occupation by the Nazi’s, Sørensen imagined a new type of playground. Instead of a carefully manicured experience, the kids would be given a designated space where they could dig through whatever junk happened to be donated to their cause. The first official junk playground opened in Emdrup, Denmark in 1943.

Junk playgrounds found an unlikely ally in a child welfare advocate in England named Marjory Allen. Lady Allen of Hurtwood was inspired by the experiments in Denmark and asked, “Why not use our bomb sites like this?” The idea was rebranded as adventure playgrounds and eventually more than one thousand of the makeshift parks were erected across Europe.

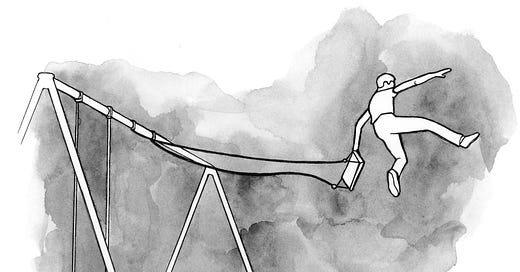

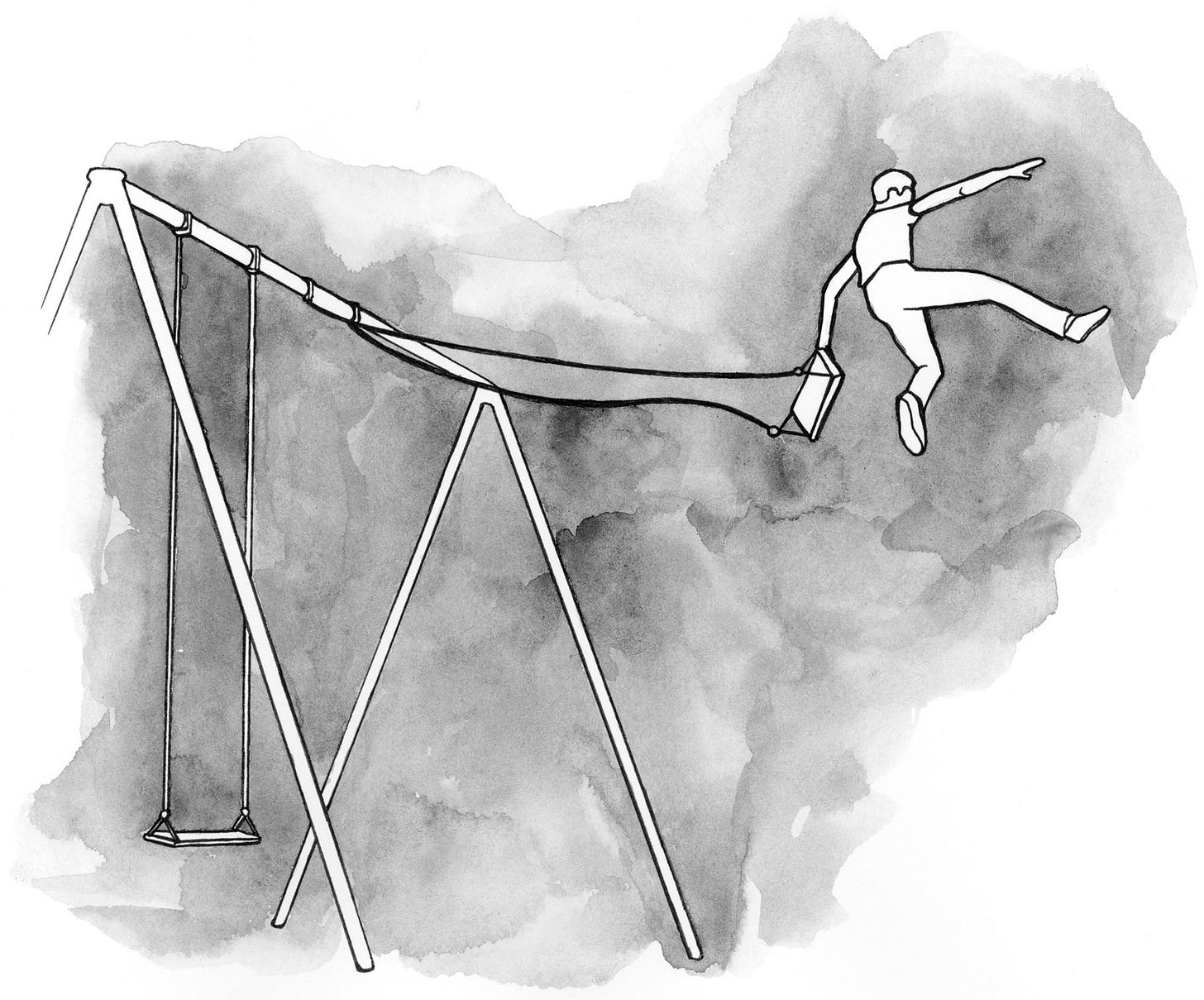

The idea was simple but controversial. Instead of engineering a play space where children are protected from the dangers of their curiosity, an adventure playground empowers kids to figure it out themselves. For parents it is a nightmare, they see their babies covered in dirt, swinging hammers, building fires, jumping off rickety structures, and manufacturing sharp objects. And yet somehow it works. Or at least it worked in Europe when this type of thing was still tolerated. Adventure playgrounds never really made the jump across the pond, and despite a few valiant attempts to bring this idea to life in America, the playgrounds of today have been standardized to include the ubiquitous swing set and slides. To do more than that is to invite lawsuits fueled by parental outrage.

Whether it is pristine playground equipment or a pile of planks, a child approaches them as user zero. Their minds, prior to being imprinted by what an object is supposed to be, naturally questions what it could be. Where adults see trash, dirt, and danger, the child sees nothing but potential.

What is a child to make of the bubble-shaped furniture of today’s playgrounds? What lessons are absorbed from the bouncy ground and mushy mulch? Perhaps it is that here the rules of Earth don’t carry punishment. That any fool can toddle into this creation and escape unscathed, that there is no penalty for folly, no cause for caution.

After the safety committee strips away the danger, they can sex it up with bubblegum graphics and bright plastic panels, but you can’t play a player, especially when playtime is a child’s only chance to escape beyond the reach of hovering helicopter parents. The protective candy coating can’t actually stop an adventurous spirit. Children are going to use that playground as a tool to hone their understanding of the world, regardless of adult intervention.

Bored by the dangerless innards of modern playgrounds and eager to test their mettle, a child will inevitably set their sights on more exciting targets. The sun-blocking gumdrop roof of the slide, absent from the designs of yesteryear, beckons exploration. And perhaps anticipating this misuse, the designer of the slide made its roof all the more difficult to assail. The child accepts the dare, setting out courageously without foothold or grip until they are perched precariously on slick surfaces, teetering above the other children and fainting parents below.

Assuming survival of this misdeed, what has the child learned? That the game is rigged, that the only way to beat it is to break the rules? That there are things that grown-ups desperately want to hide from them, and those things aren’t dangerous, no that is where the real fun resides. And assuming the worst, how long after an accident will this playground remain intact before lawsuits force more safety, more softness, more layers of bubble wrap on the wimpy playground?

It wasn’t always this way. The playgrounds of old carried clues to how to use their equipment, affordances that required only a glance to absorb. There was a time when the slide didn’t hide behind soft, pastel padding. The heights weren’t hidden by candy-colored plastic, the steps weren’t dipped in rubber, and rarely did they sport reassuring railings. The danger was right there, out in the open, exposed for all to see. Your destiny was held exclusively in your own hands should you dare to ascend their bare exteriors.

The minimalist playgrounds of the past also carried an alternate set of lessons. Here, mastering a challenge required new skills. The bare steal and tall heights were intimidating. Not hurting yourself required creativity, it forced you to wonder what small ways you could equip yourself for success. Each visit to the playground was an exercise in leveling up as you developed strength, dexterity, flexibility, and most of all courage to ascend the giant ladders and shoot down poles. And with your feet firmly back on the ground you felt pride in your abilities. You left the playground a better person, ready to conquer the next obstacle. You learned that there was enjoyment in embarking in challenges beyond your ability.

This brings us back to the concept of opacity. There is value in being able to easily grasp how something works just by looking at it. The minimalist bars of old parks are transparent because there is nothing preventing you from understanding them at a glance. Modern playgrounds are opaque because the dangers are hidden beneath layers of rubber, foam, plastic, and decoration.

Childhood represents our first attempts to master our environments. When play objects are transparent we grow up with confidence that we can understand, perhaps even build our world. When the underlying ideas are hidden, their lessons are never taught. Instead of minds that bulge with the confidence of mastery, humans grow up believing in magic and depending on others. Playgrounds aren’t the only things that have shifted from transparent to opaque. It’s everything.

In the next chapter we take a closer look at the points of contact between our mental maps and our tools. Commonly referred to as user interfaces, there is enormous complexity hiding in even the most basic tools. Understanding this will bring us closer to becoming user zero.

Thanks for reading. I am releasing User Zero one chapter at a time on Substack for free to all subscribers. Physical copies are available from Amazon. Stay creative.